Travel and Peregrination

Simone Fattal

“Culture is die-hard. Customs outlive the circumstances of their birth.”

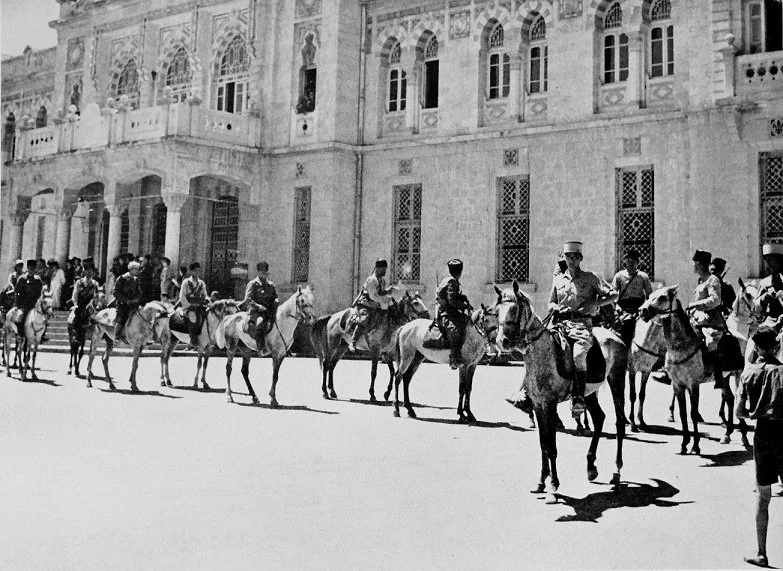

Fig 1. Circassian cavalry regiment in Damascus in 1941

The Ottoman Empire was a vast stretch of land. It went from Morocco to the doors of Persia. From Bulgaria, including Greece, to Pont-Fuxin. What we know today as Syria, Lebanon, Irak, Egypt, Libya, Arabia, Algeria, and Tunisia were all under the same banner. And in Europe, Bulgaria, Albania, Romania. All the way to Hungary.

The Ottoman Empire was a unity. This identity gave the local population a unique freedom and peace of mind. The freedom to move freely, and to identify with any of the parts of that vast entity.

The very big common denominator was religion. The majority of the population was Muslim. And Sunni Muslim. And therefore, ethnicity played a minor or no role at all. Those were times when religion was by far the main identity for anyone. Those populations felt a likeness, a closeness with their counterparts from far away regions.

We shall talk about the Syrian population. When I was growing up, I had many friends whose mothers were of foreign origin. They were mostly Turkish. But also, Slavs from Caucasia. Or Albanians. The Caucasian women were very much sought after because they had those extraordinary qualities, cherished by men everywhere, health, first of course but even more importantly the women from the Caucasian mountains were strong, fair skinned and had blue or green eyes. Enough to appeal to any man from Damascus or Aleppo.

Fig 2. Amman. 24th anniversary of Arab revolt under King Hussein & Lawrence, celebration Sept. 11, 1940. One of the Emir's Circasian [i.e., Circassian] bodyguards

The Caucasian men were also very important to the Ottoman Empire The Circassians provided entire battalions for the army, in the same manner as the janissaries, but it is a less known fact. The women, wives to whomever were able to gain their consent.

The mobility of these populations is difficult to imagine nowadays. The Syrian society provided civil governors, and military governors to the empire. The fact that young men went to Istanbul to study in the two main schools of the empire: the Military Academy, and the School for Administration, already indicates that this society was cosmopolitan. Cosmopolitan by culture, and by custom.

The empire was ruled out of these two schools. When a young man graduated from the Military Academy, let’s say, he joined the army, he could be sent to Arabia, Libya or Bulgaria. The civilian administrator could also be sent to any part of the Empire, Gaza, Damascus, or Algiers.

The nomadic roots of these populations accounts for this mobility. The transhumance routes, which since time immemorial went on the one hand from Yemen to Urfa, northwards, never stopped. And on the other hand, the route went from Yemen to Morocco, westward. Tribes moved along these routes forever. Some were settling on the way, and building some of the greatest cities of history.

And Epics, like the epic of the Bani Hilal, for instance.

Or The Epic of Zhat El Himma.

Or The Thousand and One Nights.

Another root comes from the Koran that reinforced this culture. The World is vast, the Koran says. It is an invitation to the voyage in itself. Another thing of course is the example of the hijra, meaning that if it does not work for you there, try somewhere else.

Therefore we have in Damascus, in spite of the fact that society was closed in the way that the only social ties and events were strictly family oriented, a very cosmopolitan society, by the very fact of the wider structure. Military men were called to all the regions of the Empire.

A great Syrian writer, Ilfat Al Idelbi, illustrates in her family what I am trying to describe.

Her great great grandfather was a man from Dagestan.

He had settled in Damascus and had obtained the position of leader of the Pilgrims to their annual pilgrimage to Mecca. This was indeed a very important position, as he was responsible for the safety of the pilgrims, who traveled usually with a lot of valuables. In Mecca, indeed, the pilgrims had by custom to buy gifts for all the members of their wide families. This wealth carried by the pilgrims, could provoke the attacks of tribes or individuals, who would try to rob them on the way.

And therefore he had to be a military man as much as being a responsible leader. The departure of the convoy of pilgrims was a very big affair. Banners, music, horses, and camels were part of the convoy. Their departure was witnessed by the whole city. He held the position for a very long time. The family stayed and lived in Damascus, under the name the Daghestanis.

Fig 3. Beirut 1914

The family of my best friend Hala Al Khodja, was a nomadic family. They were still in the 1950s, from a tribe that kept the annual route of transhumance from South to North. Their place of settlement was Rakka. Her father was a prince and he held for many years the position of minister for agriculture. They used to go— before the northern province was to be given to Turkey by the French, during their mandate, —to Urfa. A delightful city in present-day Turkey. Theirs was a continual voyage.

This mobility was just as present in the Christian community. In the 18th century , according to memoirs and archives, the Syriac priests traveled just as easily . From any city they would go to the seat of the archdiocese, to confer with the head of the Church, the Patriarch, who was based in Antioch. He could also go to the mountains of Lebanon, or to Damascus, to bring documents, or take some. Annual seminars were held. I read some of these archives and I was struck by the ease of travel. And its constancy. The same can be said of course of the Greek Orthodox communities and the Greek Catholics.

Fig 4. Damascus

Culture is die-hard. Customs outlive the circumstances of their birth. This is why even in the 1950s, so many people in Syria spoke Turkish when the mother was foreign. By then, Albanians and Eastern European were added to the traditional Turkish background, as a place of origin, the new cities where the young men traveled to study.

My grandfather was a tobacco inspector. He roamed Syria and Lebanon on his horse, from field of tobacco to the next. My father was educated in Vienna along with hundreds of young men from Syria before World War First.

The German bankers and Austrian businessmen who had settled in Syria during the Ottoman Empire sometimes married Syrian girls, and that was the case of my great grandmother.

Fig 5. Circassian lady

In my own experience I traveled every week from Damascus, my family home, to Beirut, where my boarding school was. And the fact that I was so used to go from one place to the other, to cross borders, because by then a military checkpoint with two stops each ,—had been installed between Syria and Lebanon (!) gave me a mobility, and I would say a sense of freedom— in spite of the boarding school being a prison, in itself. But I can say that this was the only good side of that upbringing.

I cannot stress enough the fabulous advantages that this society gave their men. No obligations except what their morals required of them. They had no obligation. A man could go to the pilgrimage and stay away for years. He would marry on the way, but came back if he felt like doing so.

Some disappeared, but the majority held their accepted obligations very promptly. The extended family was there to monitor all these behaviors.

Looking for a Circassian lady for one’s son is still being done in Lebanon today, but rarely, I must say. I have to add that the pilgrimage, (for both Christians and Muslims — the Christians went annually to Jerusalem, and the Muslims to Mecca—had sowed in society the idea of peregrination.

Peregrination is also one of the ascetic practices some Sufis choose to perform.

It is one way of looking for God.

We should not forget the influence of literature.

The Thousand and One Nights, which was recited and told over and over again in the cafés, in Damascus, or in Jameet El Fna in Marrakech, and later in books, is full of examples of travel. It starts with the king being away. And then Djinns arrive from nowhere. Sindibad travels great expanses of sea routes. He goes to India, to China. To the Maldives.

Commerce with China and India, started already during the Byzantine Empire, and that also never stopped. It is called The Silk Route. The caravans going from Arabia, to Syria, to China, also never stopped . The sea route also went from Arabia to India and China.

We find ouds, and cithars in the Japanese collections of religious temples going back to the 7th century. The trade with China and all the other places in between was held by the Arabs and their caravans, when not on their boats. This monopoly of the trade routes, —that ended on the Mediterranean when the Italian boats came to take the goods to Europe,— Italians and Spaniards wanted to break. It is the motor that pushed them to work towards discovering the route to India.

Fig 6. Ulfat Idilbi

This route to India first started before the Roman Empire, the Frankincense and the spices came from Arabia and were transported to the Mediterranean’s by the Nabataeans. This is how we have the Nabataean cities of Al Oula in Arabia, or Petra in Jordan.

The temples in Greece or in Egypt had a huge need of frankincense and of spices. This constant voyage brought with it polyglot societies . It was natural to speak many languages in any household. The Afghanis wrote in Arabic and so did the Persians. Arabic was the language of religion, and of philosophy.

Let us remember the story of the Queen of Afghanistan Soraya Al Tarazi. Soraya Al Tarazi was born in Damascus in 1899. Her father was from Afghanistan, her mother was a Syrian from Aleppo. Her father was the Muezzin at the great mosque of Aleppo. Soraya lived in Damascus all her life and then visited Afghanistan to meet the Prince Aman Allah Khan. The prince fell in love with her and they got married; she became Queen of Afghanistan in 1926. She was the First among the Muslim queens to attend national events with her husband, to be present at horse shows or other sports events. She was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Oxford for promoting the education of young girls.

Until a few years ago you could still board buses in Damascus to go to Afghanistan.

What about today?

With the advent of “Independent Republics” came the borders and the obligations. The way of life got restricted to the actual country, recently created, usually, and even more to the city that you lived in. Society became less nomadic and less free. Colonialism gave a pattern to society. The upper classes who could afford to travel could send their young men and soon enough the women to study abroad; this time to the country which colonized that specific country. For Instance the Iraqis went to England, whereas the Syrians and the Lebanese went to France.

Some married foreign women but not at all to the extent of the generations before I would say before World War First.

Even my great friend, Abu Nazir, the glass blower, who came from a very traditional class, married a woman from Tripoli, Lebanon. And when they visited Kosovo, they were greeted like members of their family.

But then the modern wars happened, the geography shrank, every day a little more, a little more. First from country to country, then from city to city, then in one city, from west to East. Checkpoints, danger, rules, visas, restrictions, A visa to leave one’s country and another to re-enter, another to enter the neighboring country. And so on.

What happened to this society? What happened to our countries? What kind of fury, and unfairness has settled over us?