Anamnesis for the present time: Crossed perspectives on Route 181 by Eyal Sivan and Michel Khleifi

Luc Bachelot and Rose-Marie Godier

“… only the Other can heal, and the movement towards him.”

During the summer of 2002, Palestinian filmmaker Michel Khleifi and Israeli filmmaker Eyal Sivan decided to embark together on a quest for what may not quite be an utopia: a common country, undivided, that they named Palestine-Israel. The chosen format for this documentary, as with Road One/USA directed in 1988 by Rober Kramer, is that of the road movie. The two films indeed borrow to this cinema of fiction some of its prerogatives: those that establish the road as “a place of the identity quest and the journey of two people[2]”.

Road movies, or at the very least those that focus on traveling across the United States, can also be seen as revisiting the movement of previous generations of immigrants, who have shaped the country’s identity.[3] We could say that both Route One/USA, and Route 181 “reenact” the founding myths of their respective countries: both documentaries are not as much an attempt to challenge a utopia through surveying the real territory, as they are a way to stress the real territory, by taking into consideration the utopia.

The invention of the place

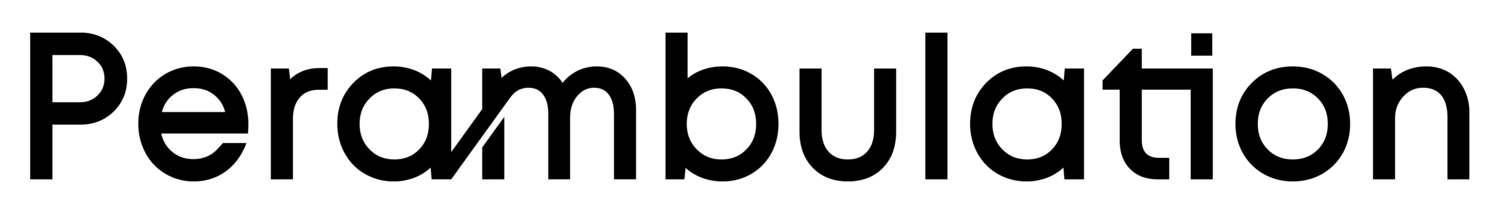

Fig 1. 1947 partition plan : the map with the routes

Truth is, this “road 181” does not appear on any map. It is the drawing of complex borders between an Israeli state and a Palestinian state, as planned in the 181 resolution of the UN in 1947, that Sivan and Khleifi establish on the “road” in order the explore their country, just the two of them.

In the eyes of the two directors, this is indeed a journey, starting from a “founding” road similar to the Road One undertook by Robert Kramer in the USA – the only difference being that the layout decided by the UN in 1947 was essentially that of a partition. For Sivan and Khleifi, as for many contemporary historians[4], 1947 is the moment when everything started. Let us remember that this resolution, rejected by a majority of Arab countries, led to the war of 1948, which continues to this day. And for our directors, by choosing “to put borders on the hills and on the plains, on the mountains and in the valleys, we also durably inscribed them in the minds and hearts of two people and in the collective unconscious of these two societies[5]”. Establishing this fault line on “the road” is the first movement toward potential healing.

Route 181 would then fall within what Didier Coureau has defined as a “filmic rewriting of the world[6] ”. Using the gap that the journey assumes, it is able to extract itself from immediate reality and to offer the spectator a space where thoughts flow, beyond the raw emotion that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict inevitably provokes.

“A traveler is a kind of historian…[7]”

Fig 2. The road in the West Bank with map on dashboard

Under the guise of geography, Route 181 is first and foremost a journey through time. And while the road is based on memory, it is first a struggle against the landscape’s amnesia. Route 181 hence dwells on the ruins that appear here and there, on the isolated marks of villages scattered across its itinerary, as well as the souvenir of places’ names, now erased, but that a question brings back from memories – that of the Palestinians of course, but the Israelis’ as well.

To be a historian, Walter Benjamin wrote in On the concept of History, means to “brush History against the grain[8]”. To follow the layout of 1947 allows for the acute friction between several temporalities: that of 1947, of the 1948 war; that of the Nakba as well as that of the Shoah; that of the multiple exoduses and the wars; that of 2002, the second intifada and the film’s present time; finally that of fragile, stubborn temporality of the utopia.

On the road

Fig 3. The two directors seen from the back

If the purpose of the two directors is to replace “the idea of the partition by the idea of sharing”, the utopia is already implemented in the filmic apparatus of this documentary, since Khleifi and Sivan decide from the outset to share the film, as a prefiguration of the potential sharing of the territory. By deciding to make themselves nomades, similarly to the bedouins of the first sequence, the two directors voluntarily distanced themselves in favor of the geographical and ideological margin, a space and a time to reinvent. The opening credits announce the general economy of the film: our vision will not be one of adhesion, but a semi-subjective one, inside an “elliptic” film, because it is built out of two homes.

In Route 181, the road movie format also allows to bring spectators along, to communicate to them this mobility requirement – this necessity to get rid of clichés, of fixed and simplifying stands: here, the journey is a fiction, an apparatus of representation, that allows for a change in its spectator’s perspective on reality.

Furthermore, for Sivan, the bringing together of images, in other words editing, is an injunction to think: it allows for a continuity, on a narrative line, of disjuncted fragments. Narrating then allows us to reconfigure History. For him, sharing the archive is already the beginning of a potential dialogue.

The journey also installs a vacancy, both for the directors and the spectators: the car’s interior separates us from immediate reality, news reaches us muffled by the radio speakers’ voice. The journey breaks with the daily flux of events, and places us in a suspended time, a fallow time of sorts, able to welcome all sorts of times.

And while this film reenables, around 1947, the layers of a painful and rather recent past, its very form seems to arise from a much more ancient layer, burrowed into the thousand-year-old memory of this Middle-Eastern territory – a layer even more ancient than the biblical time claimed by some of the film’s protagonists. A form that would unconsciously come to haunt the film. One might say that Route 181 keeps the imprint of the first historical epic that the Mesopotamian civilization wished to record on clay tablets. The journey and roads were already there three thousand years ago for Enkidu and Gilgamesh’s stubborn quest of what constitutes our shared humanity.

Foundations

This epic about the king of the powerful Sumerian city of Uruk (modern-day Iraq), its companion Enkidu, and their feats could turn out to bet the model of our modern road movie – not only because it is the oldest epic ever written in the history of humankind, not even because the geographic zone where this extraordinary adventure took place is the same one scoured by Sivan and Khleifi, but because its very structure and the content of its episode present the most evident characteristics of a road movie: the journey is undertook by two ; it results in a series of failures; it ends up imposing a principle of reality that is ultimately confused with what could be called the “syndrome of the quest for immortality”, working on every tentative to control time, even if it is not explicitly declared.

Fig 4. Tablet recounting one of the episodes of the epic of Gilgamesh

The epic tells us about a certain reality, but also about the conviction that what happens goes beyond it, can transform it or establish a new configuration of the world.[9] This foundation does not establish itself easily: departures, ripping apart, pitfalls-ridden paths, mortal combats, all seem to be its premises, all necessary and marked by the seal of violence. But isn’t that the principle of every foundation?

The standard version of this epic established around 1300-1200 BC. is the end result of a long process of elaboration that lasted almost 2000 years.[10] It came to be in Mesopotamia, in the south of modern-day Iraq. For environmental reasons – an alluvial plain without stones or wood, near the immense Arab-Persian desert – Mesopotamia was at the same time the land of sedentary anchoring and the foundation of the first cities, but also that of travels and constant movements, and of nomadism, which greatly facilitated all sorts of exchanges and the diffusion of skills and knowledge.[11] This is one of the characteristic features of this region. The epic of Gilgamesh draws its richness from the conjunction of these two different cultural traditions. Besides, it sets the stage for two drastically different characters, Gilgamesh and Enkidu to embark together on an adventure. They undertake it in order to oppose the difficult fate imposed by the gods.

Two grand episodes make up the epic[12]:

the journey of two towards the mounts of Lebanon and the solitary quest for immortality. The two procedures are structurally linked and only make sense one in relation to the other, as we will see.

First episode. Gilgamesh is a young king. He is particularly energetic and even tyrannical. Furthermore, under the pressure of the city’s inhabitants unnerved by so much violence, the gods decided to create his double who was also his opposite: Enkidu. While Gilgamesh is the man of the city, Enkidu is the man of wild nature. He lives naked, amongst the steppe animals, sharing their fearsome strength and eating like them. In the city, Gilgamesh therefore ends up face to face with a being as feisty, strong and courageous as himself.

Fig 5. Gilgamesh and Enkidou Umbaba

A merciless battle begins until exhaustion is reached. In the end, the two fighters mutually recognize their value, form a friendship and decide to go on an adventure together, towards the West, which is to mean towards Lebanon, probably to go find what is missing at home in Uruk, wood (the very symbol of wealth) – and hence to go towards the country of gods. Several pitfalls punctuate their expedition, notably the meeting with some sort of ogre, Humbaba, who is gifted with extraordinary and terrifying powers. Joining forces, they knock him down and come back victorious to Uruk with the precious wood. Seduced by the strength and courage of Gilgamesh, the goddess of Love, Ishtar, asks him to become her lover. He refuses! Out of spite, the goddess causes Enkidu’s death.

Gilgamesh is overwhelmed by this disappearance and revolted by the mortal condition of mankind. He decides to go on a quest for immortality. Gilgamesh leaves for the other side of the world, East-bound this time, in order to find immortality. Its secret will be revealed to him by Utnapishtim, the only human to have survived a flood caused by God to exterminate humankind. Before reaching this immortal being, he must face several obstacles. He finally obtains from Utnapishtim the plant of eternal youth; but a snake steals the plant from Gilgamesh. The hero then returns to Uruk, empty-handed, but now a man of experience, and even of wisdom. He understands that the only way to reach eternal life is to leave behind the tale of his feats as well as lasting monuments. He then builds the ramparts of Uruk.

Just as well, the road movie, the modern avatar of the epic, is also a founding story. The quest for a better future is most fruitful when it is not undertaken by only one man. Khleifi and Sivan’s approach remind us of this challenge: an adventure full of friendly magic that tells us what was achieved by two individuals can also be achieved by two communities.

The deceptive and founding violence

The Israeli-Palestinian documentaries and the Sumerian-Akkadian epic continue to show us that unity is never naturally available, that we must constantly be building it. Disparity, fragmentation, crumbling all come first. Coming together always requires work that is strife with a series of failures; an extremely violent situation that is probably necessary to the institution of what is common, and besides, to any foundation.[13]

In Route 181, the violence of recorded commentaries echo the real violence: we are in 2002, at the height of the wave of suicide-bombings. But besides this direct and apparent violence, there is also indirect violence: that of the past, unsurpassable, like the Shoah for the Israelis or the Nakba for the Palestinians. These sufferings, that cannot be confused, bring about new violences each day and exacerbate the tensions even more by being historically placed under God’s arbitration. For many Israelis (and even some christian communities as shown in the film[14]) the land of Palestine was given to the Hebrews by God; which cannot be questioned. For the Palestinians, whether muslims or christians, having had to cede their land is an unacceptable injustice.

Sivan and Khleifi then want to make peace by establishing a common nation, but that can only happen at the price of sacrifice,[15] which the abandonment of their exclusive sovereignty over this land represents for both Jews and Palestinians. This is indeed a sacrifice, a loss, but if this struggle for the unification of the two communities was to be won, then the violence that would have taken place would be what Benjamin calls “founding violence”, which founds not only rights but also justice.[16]

« Do not forget all of the roads I roamed with you…[17] »

The road movie is a quest that aims to found a new entity or identity. This foundation is perhaps more similar to the conquest than to the simple quest. A solid foundation indeed suggests that the journey is always necessary in order to acquire elements that will never be at arm’s reach. It is from this outside that must come support and solidity. Auto-foundation is also condemned to crumble.

The outside is part of space (Gilgamesh must go to the world’s edges, both East and West), but also of time (it is to Utnapishtim, survivor of the Flood that took place at a very ancient time, that Gilgamesh must ask for help). For Sivan and Khleifi, before reaching the union of the country and the communities they work for, it was necessary to come back to the source of the actual conflict: 1947.

This future to be built must root itself in the otherness of time and space, but also in the confrontation of two lives, two experiences, two communities, incarnated by two individuals. The establishment of a “one” always suggests the intervention of the “two”. As Barbara Cassin puts it so well: “We are at home only where we are recognized. We can never be at home when alone! We need the gaze of others that recognize us to truly be at home[18].” We build our identities only by taking the other’s identity into consideration. That is what the epic and the road movie remind us of.

[1] Michel Le Bris, Fragments du royaume (“Kingdom Fragments”), in Collective, Pour une littérature voyageuse (“For

[2] Bernard Bénoliel et Jean-Baptiste Thoret, Road Movie USA, Paris, Hoëbeke, 2011, p. 96.

[3] See Bernard Bénoliel and Jean-Baptiste Thoret, op. cit., p. 29.

[4] We are thinking here of Benny Morris or Ilan Pappé, who are part of the “new historians” group in Israel: the opening of British and Israeli archives in 1998 led to a reevaluation of the war and the events of 1948.

[5] See Eyal Sivan’s official website, http://eyalsivan.net

[6] Didier Coureau, « La Réécriture filmique du monde » “The filming Rewriting of the world”, in René Gardies (under the direction of), Cinéma et voyage “Cinema and travel”, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2007, pp. 259-274.

[7] François de Chateaubriand, Itinéraire de Paris à Jérusalem, et de Jérusalem à Paris, “Itinerary from Paris to Jerusalem and from Jerusalem to Paris”, Paris, Gallimard, 2005, p. 56-57. Thanks to Marie-Christine Gomez Géraud for drawing our attention to this quote from the preface of the Itinéraire which she placed at the beginning of her Presentation of: Marie-Christine Géraud (under the direction of), Research Centre of the French Department of Paris X Nanterre.

[8] Walter Benjamin, Sur le concept d’histoire “On the concept of History”, in Œuvres III, Paris Gallimard, 2000, p. 433.

[9] See Hegel, Principe de la philosophie du droit “Principles of the philosophy of law”, Critical edition established by Jean-François Kervégan, Paris, PUF, Quadrige Editions, 2013, § 350. For Hegel, the epic tells us about a certain reality and the heroes are led to found States. A proposition he also touches upon in Cours d’esthétique “Aesthetics Lecture” (Translation Lefebvre et von Schenk), T.III, Paris, Aubier, 1995, p. 309-310.

[10] We will refer ourselves to l’Epopée de Gilgamesh, Le grand homme qui ne voulait pas mourir “The Epic of Gilgamesh, the great man that did not want to die”, Jean Bottéro’s seminal work (Paris, Gallimard, 1992) which delivers both a complete translation of the text and a very rich and abundant introduction as well as many comments for a perfectly clear reading of this first work.

[11] This characteristic was quickly recognized by all specialists of this cultural era. It rightfully remains central in all analyses of the ancient Near East. To get a better idea, we can refer ourselves to the proceedings of an international symposium that was entirely dedicated to it in Paris in 1991: La circulation des biens, des personnes et des idées dans le Proche-Orient ancien. “The circulation of goods, people and ideas in the Ancient Near East”. Texts collected by D. Charpin and F. Joannès, Paris, Research on Civilisation Editions , 1992.

Concerning the epic of Gilgamesh, we can find versions of it in Meggido, near modern-day Haifa, as well as Jericho: its era of diffusion extends from Mesopotamia to Palestinian and until Anatolia, at the court of Hittite kings. See Bottero, op. cit pp. 45-48.

[12] Here we are only very schematically mentioning this epic, by retaining the elements that can help us understand the proposed similarities to the road movie; which is only confirmed by the complete reading of this story with its many twists and turns.

[13] See on this subject Walter Benjamin, Pour une critique de la violence “The Critique of Violence”, dans L’homme, le langage et la culture, ”Man, language and culture” Paris, Denoël Gonthier, 1974, p. 37:

“It is above all necessary to establish that an elimination of conflicts entirely stripped of violence can never reach a contract of legal nature. That is because the latter, however peacefully it may have been concluded, leads as a last analysis to potential violence.”

And the commentary proposed by Jacques Derrida in Force de loi. Le “fondement mystique de l’autorité” “Force of Law: The Mystical Foundation of Authority”, Paris, Galilée, 1994, p. 112 and p. 115:

“There is no contract that does not have violence both at its origin (Ursprung) and end result (Ausgang). (…) In short, we have just seen that in its origin as in its end, in its foundation and its conservation, rights are inseparable from violence, whether immediate or mediated, present or represented.”

[14] Let us recall the Ges kibbutz episode in the film, where a group of American protestants from Kansas are planting olive trees (Le Centre, 00.29.00), under the direction of a rabbi and his wife.

[15] Here, we cannot do without René Girard’s book, La violence et le sacré, “Violence and the sacred” Paris, Grasset, 1972, which is mainly dedicated to the founding function of sacrificial violence.

[16] That is what is at stake in Walter Benjamin’s text, previously cited or the “Pluralisation of hegemonies”, advocated by Chanal Mouffe, Agonistique, Paris, Beaux-Arts de Paris, 2014, p. 17.

[17] Epopée de Gilgamesh “The Epic of Gilgamesh”, Enkidu’s lamentation, René Labat’s translation, op. cit., p. 193. In Jean Bottéro’s more recent translation, op. cit., p 146 :

[Moi qui, en ta compagnie

[Avais pas]sé tant de pé[r]ils,

Sou[viens-toi de moi], (mon) ami :

N’[oublie] rien de ce que j’ai enduré ! »

[18] Barbara Cassin, La Nostalgie, Quand donc est-on chez soi ? “Nostalgia, When are we ever at home?” Paris, Fayard, 2015.