What Remains: On Vicky Pericleous’s The Idle Fountain

Cathryn Drake

“Where we make our home, however, is determined by force, fancy, or chance.”

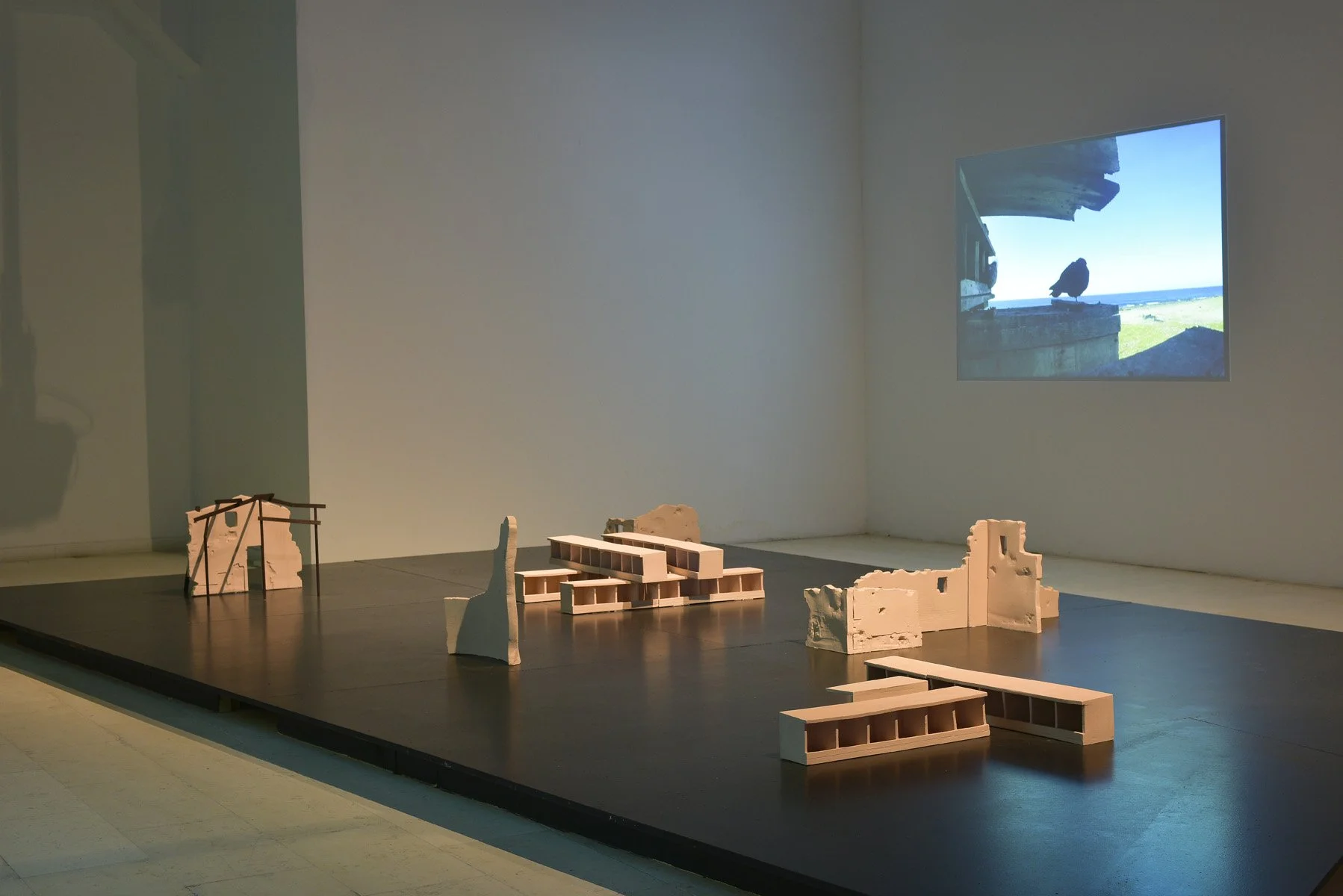

A Minimum of Visible World, 2018, ceramic, wood, 3 video projections, dimensions variable. Installation view, The Presence of Absence, or the Catastrophe Theory, Nicosia Municipal Arts Centre, 2018, curated by Cathryn Drake.

Photo credits: Nicos Louca.

Our cosmic journey is infinite, yet we live as if there was no tomorrow. We are, above all, motivated by the fear of death. Human dwellings have evolved across time from fundamental shelters to complex architectural structures that perpetuate illusions of permanence and order, cloak insidious systems of influence, and keep the cycles and rhythms of nature at bay, if only temporarily. The contemporary home encompasses the entire built environment in a network of phenomena that impacts the most remote corners of the earth. And capitalism is our religion. So every now and then the planet brings on a crisis to remind us that the natural environment is the quintessence of the human condition and the state of its health, a reflection of our own. The Covid-19 pandemic has brought home once again the irrelevance of borders and boundaries, both biological and sociopolitical, between all living beings.

Where we make our home, however, is determined by force, fancy, or chance. When Cypriot artist Vicky Pericleous accidentally came upon the abandoned ruins of Petrofani, a village evacuated by Turkish Cypriots forced to migrate north, set in a verdant landscape populated by grazing sheep, it seemed to her as if it was not the end of a story, but rather the beginning of something else growing out of the raw earth. Her work “A Minimum of Visible World” (2018), produced for the exhibition The Presence of Absence, or the Catastrophe Theory, at the Nicosia Municipal Art Centre (NiMAC), is a miniature reconstruction of the settlement that takes its title from Jorge Luis Borges’s The Circular Ruins. The short story, published in 1940, evokes an abandoned structure adapted as a sacred shelter for a refugee. In Borges’s tale a wizard arrives by boat at the charred remnants of a temple to a deity of a vanished civilization. But in the end, the ruins are in turn ruined again, destroyed by fire.

The context of modern Cyprus, a geopolitically strategic territory claimed as a homeland by both Turks and Greeks, exemplifies the present socio-political state of the world as a place fractured not by cultural differences but rather by the myth of nationalism in the service of colonialism and economic exploitation. Since 1974, when Turkey invaded the island in the wake of nationalist violence and an aborted coup by the Greek junta, most of the population has been displaced within its own borders, exiled just miles away from their homes. In the intervening years since the occupation, the demographic balance north of the de facto border has been realigned in favor of immigrants coming from Turkey, while Turkish Cypriots have fled in different directions.

The LED lights from gigantic newly built mosques are most visible from the highways at night, alongside the neon signs of bordellos. UN peacekeeping forces patrol the buffer zone, known as the Green Line, and distinct areas designated as British Overseas Sovereign Territory, a legacy of colonialism, are conspicuous in grassy knolls dotted with oddly quaint houses and English street signs. The latest foreign influx to the island consists of wealthy Russians purchasing “golden passports,” many fleeing criminal prosecution or taxes.

Anti-model for a Future, 2020, fibreglass, fake gypsum, fake-mosaic, 140 x 197 x 60 cm, Installation view, Art Seen Gallery, curated by Maria Stathi. Photo credits: Nicos Louca.

Yet in 1998, when a boat of refugees arriving on the shores of Cyprus from Lebanon was rescued near an RAF airfield, its 20 passengers—from Syria, Iraq, Ethiopia, and Sudan—were taken in by the British military base Dhekelia and housed in Richmond Village, a group of bungalows previously judged uninhabitable and vacated by officers. Although they were granted asylum, the six families lived for 20 years in these temporary accommodations—on a desolate scrap of land with faded street signs bearing names such as Maples Road, Cornwallis Avenue, and Waterloo—while the governments of the United Kingdom and Cyprus fought over which country was legally responsible for their fates.

The British government argued that the refugee convention of 1951 was never extended to Sovereign Base Areas (SBA), so the families had no grounds on which to seek resettlement in the UK. Meanwhile, the houses contained harmful levels of asbestos, which led to cases of cancer, and children were born and raised in the limbo of statelessness. Artist Efi Savvides recorded the stories of the families for her project “The Empire Is Perishing; the Bands Are Playing.” Years before the British court finally granted the families permanent residency in 2018, the UNHCR found high levels of anxiety and depression among them. And while British authorities congratulated themselves on the humane ruling, the Home Office published the following caveat: “The Supreme Court judgment is clear that refugees who arrive on the SBAs on Cyprus have no automatic right to come to the UK.”

Pericleous conveys the history of human folly in her ongoing series of sculptures, drawings, photographs and videos that expose alternate dimensions of existence through the ruptures of disjunctions in time and space. The artist employs the trope of Modernism to portray a rivetingly familiar dystopian present constructed out of the remnants of a productive past too barren to bear a fruitful future. Through the recurrence of images across different contextual narratives, the work destabilizes our perceptions of the physical world and synchronizes our gaze to its natural rhythms. Pericleous encapsulates the mechanics of the universe through material drawn from her surroundings, almost always encountered by chance in archives or on the terrain of the Mediterranean island of Cyprus.

A replica of a 1960s purpose-built pigeon house found in Paphos (the site of an ancient temple to Aphrodite), was placed among the miniature models in “A Minimum of Visible World”. In that way Pericleous highlights the tension between the utopian ideals of Modernism and its failed or obsolete spaces—as much as between the pursuit of permanence and the inevitability of change and displacement. When I look at a building, I nearly always envision its future: the inevitable cracks, decay and obsolescence, abandonment, collapse, and eventual decomposition. Footage recorded by CCTV cameras mounted on the remains of Petrofani was projected onto the walls of the exhibition, so that the spaces, real and imaginary, merged seamlessly to form a third space inhabited only by the viewer. What became apparent is that the fragments of the village have become an avian habitat.

Ruins carry sentimental fascination as embodiments of past eras while eliciting the notion of place as both temporal and subjective. Although they are often appropriated and repurposed to serve the ideology of political regimes, what is left is never representative; it is simply what remains, and nothing more. And in this chain of causality, there’s no stopping their transfiguration into something else completely.

The Eternal Return of the Sun, 2020, industrial tiles, ceramics, 2020, Art Seen Gallery, curated by Maria Stathi. Photo credits: Nicos Louca.

As Turkish aircraft bombed the port town of Famagusta in August 1974, 15,000 Greek Cypriots fled the glamorous enclave of Varosha, assuming that they would be able to return after the conflict. Its fenced-off villas were left to looting and decay for 46 years, and just recently the contested territory has been opened up as a perverse tourist attraction by the unrecognized Turkish regime in a political provocation that has triggered an uproar.

If a brief glance into the vacant windows of modern ruins through a chain-link fence was deeply distressing, then imagine walking among the former homes, high-rise hotels, and nightclubs; it would be unbearable. On the opposite coast, the Mavi Köşk (“Blue House”) is a bizarre yet more palatable historical site, managed by Turkish soldiers. Built in 1957 by Paulo Paolides, an arms smuggler and lawyer to former president of Cyprus Archbishop Makarios III, the fully furnished Modernist villa looks as if it hasn’t changed one bit since the day its owner escaped the invasion through a tunnel hidden behind his bed.

At the Art Seen gallery, in downtown Nicosia, Pericleous installed “The Idle Fountain,” a constellation of works whose associations and allusions reverberated beyond the physical space into myriad spatiotemporal dimensions. The centerpiece was the sculptural Anti-model for a Future (2020), a spiral truncated midair and supported by a slender arc poised on two legs. Made of white fiberglass, the spectral helix is an architectural fragment thrice removed from its original content—an image of which the artist found in an encyclopedia—a model fashioned after a rendering by architect Eleni Loizou’s 3-D copy of a diving tower for a tidal seawater pool at the Centre Balnéaire Georges Orthlieb, in Casablanca. Designed by architect Maurice L’Herbier, the ambitious sports center was built in the 1930s, during an economic boom triggered by the postwar colonial development of Morocco, and then demolished in the 1970s, giving way to the equally monumental Hassan II mosque. Divorced from its doubly ambiguous context, the amputated sculpture represents the contextual isolation of Modernism, while its form symbolizes both infinity and temporality.

We refuse to face the finitude of our form even as we accelerate our collective demise, preserving what aligns with our immediate needs while supplanting numinous nature with an illuminated screen so glaring that it blocks our vision. Casa (2020), a ghostly drawing of the Casablanca pool rendered in bright yellow pastel and pencil, resembles the yellow stain that lingers in the eye after looking at something in the brilliant sun. It is like the reflection of a memory, an afterimage of a no longer existent object, and yet there is a proximate concrete object, a copy of the original diving tower, that it echoes too. Representation is anyway never perfect and always subjective, depending entirely on partial perspectives plucked from the framework of historical time.

Ultimately, the copy becomes the original. As an object out of context, with no pool full of water to signal its function, the sculpture Anti-model embodies the perpetual evolution of matter. The gyrating stair doubled by a slide suggests a slow step-by-step ascent to the top followed by the inevitable dizzying descent. The trajectory of the sculpture is perceptible only from a distance, not from within. From above it is a circle, losing its inexorable progression and ending where it began, like the mythical Ouroboros—continually devouring and being reborn from itself.

The Image’s Tail, 2020, two channel video, sound 8 mins 13 secs. Stills from the video.

Forms appear in different proportions and overlapping proximites, evoking the cyclical nature of things and the endless repetitions of history. In The Eternal Return of the Sun (2020), white institutional tiles covered the entire floor of the space, interrupted only by criss-crossing pathways of lavender converging in a corner with golden yellow to form a radiant curve evoking a sunset. One lavender path extended toward the entrance, gesturing to an identical design on the pavement of the adjacent commercial complex—a bankrupt 1990s building formerly housing corporations that collapsed during the financial crisis of 2013. The distinctions between past and present, here and there, familiar and strange, fiction and reality disintegrate in the stark light of the space.

There’s no end to entropy; it is the material manifestation of geological time. You dig in one place and the discarded rubble forms a mound elsewhere. In the two-channel video The Tail of the Image (2020), transmitted only in the virtual space of the Internet, a fan-shaped window mirrors the form of a peacock’s tail. A black void slowly recedes across the screen to reveal a spiral staircase ascending the gutted grid of the commercial building next door, the source of the tiled pattern evoking the sun’s movement on the wall of the gallery. The window adorns a Turkish-Cypriot building in Paphos, abandoned in the 1970s and presently used as an office by a Greek Cypriot. The sunlight and shadows mutate and move across its facade to reflect the revolutions of the planet and the passing of time; when the neon is extinguished, the white window frame resembles bones, a sort of memento mori.

The imagery continues to segue and dissolve in a poetic trajectory across different locations in Cyprus: Residential apartment blocks are reflected in the glass of a corporate high-rise, a palm tree entering the frame as if an unruly intruder. A medieval fortress and a modern apartment building correspond and converse as cars and people pass from one to the other, disappearing and then emerging from behind a pile of rubble on a construction site. Finally the spare geometry of the urban buildings softens into the lush foliage of a forest, where the relentless patter of the pouring rain drowns everything with forgetfulness, as if a reminder that we are perpetually destroyed, cleansed, and reborn. A lone peacock settles on the tin rooftop of a forlorn village house in disrepair; a neon light flashes in the window as if a dysfunctional fixture on the verge of burning out. The only living presence is the bird—a symbol of resurrection and immortality.

The Image’s Tail, 2020, two channel video, sound 8 mins 13 secs. Stills from the video.

The good news is that there is no death in the sense of an ending, only matter in a process of never-ending transformation. Idle Fountain (2020) features two objects made of clay and stone shaped by the sea, found on Cyprus’s Paramali Turtle Beach and then tweaked in the hands of the artist. Set on acid yellow surfaces atop shiny white-tiled plinths, they bring to mind fossils on display in a museum or shrunken heads awaiting dissection in a scientific laboratory. Nothing in our world is original and everything returns to the formless state from which it began.

“The idle fountain” is an image drawn from Borges’s poem “Elegy for a Park” (1985), an ode to the present as a continuum: “The stopped clock, the tangled honeysuckle, the arbor, the frivolous statues, the other side of evening, the trills, the veranda and the idle fountain are things of the past. Of the past? If there’s no beginning, no ending, and if what awaits us is an endless sum of white days and black nights, we are already the past we become. We are time, the indivisible river.” Yet physicists know that time, a concept we concern ourselves with obsessively, does not really exist as such: past and future are illusions; there is only a perpetual present. The fluid hum of what we call time is beyond the limits of our perception precisely because it is inextricable from the rhythm of our own existence. As an incomplete sentence, the stalled fountain symbolizes both stasis and flow—like everything, it moves even in its state of obsolescence. There is nothing static in the universe. The only way to live is to surrender to the journey and spin in harmony with the world. As the Epitaph to Borges’s poem begins, “We are already the oblivion we will be.”

Cathryn Drake is an American freelance writer and editor focusing on the arts, architecture, and culture.