Colomna Diary

Alexandra Paperno and Sveta Shuvaeva

By the will of fate in September 2020 as part of their quarantine self-isolation artists Alexandra Paperno (Sasha) and Sveta Shuvaeva found themselves in medieval town nearby Moscow. The text recounts the experience of living in new circumstances and their forthcoming project “The House on Chicken Legs” which will open in Colomna in June 2022.

Black and White

The words “a big, fat grey butterfly” resound inside my head in the voice of the only remaining audio recording of Yury Olesha, breaking through the loud and insistent beating of wings. These butterflies are actually grey-black only on one side; on the other is a beautiful drawing, the kind that we called “peacock eyes” as children. They fly in through the ventilation window of our little house and bang against the glass, creating a constant nervous noise, and we don’t know how to let them out: you can’t open the window because the winter frames were put in and the carpenter is fixing the summer ones.

This is our first summer in this house. We moved here on New Year’s. Number 13, Artillerymen’s Drive: a quarantine spell that Misha and I are under. The emptiness of long, straight streets in an old town outside of Moscow, a crooked wooden house and garden dating back a century and a half—all of this seemed like the only possible heaven on earth at the beginning of the lockdown in spring 2020 from the perspective of our Moscow apartment. We bought the house and tied ourselves to an unknown space where we spent this year. Now we’re in the midst of a very hot summer. I ride my bicycle and remember these streets when they were frozen. It was practically impossible to walk or drive on them—a real skating rink! Then the snows came; it was as if the house was about to drown in a snowdrift. In the middle of April, we couldn’t believe that this dirt-blackened snow pile would ever melt, then suddenly it was gone, replaced by lilac and jasmine. There were a lot of surprises this year, and nobody knows what turns this trip will take from here.

Sasha, July 2021

***

“To Moscow … one … just one way … two hundred eighty-eight …”

I mumble to myself, methodically tossing coins into the machine at Staraya Colomna. The metal cabinet swallows the money, but has no intention of printing a ticket.

I turn my head toward the gates and loudly announce to the sleepy guard,

“No money and no ticket. What do I do now?”

“The one on the right’s broken, you know … You’ve got to go to the ticket counter and call an employee. Go ahead, I’ll watch and make sure nobody touches it.”

In the waiting room, full of orange light, the ticket window shone like a blue beacon. After listening to my plea, the woman at the counter yelled at the open door behind her,

“Katya, we need your help! The machine’s acting up again.”

Katya emerged from her aquarium in uniform and silently commanded me to follow her back to the gates.

“This one?” she asks, pointing at the machine.

“This one,” I nod.

Katya calmly delivers a well-rehearsed blow to the cabinet with her fist. Upon hearing the sound of coins, she quickly returns to the station building without counting them.

“But miss, there’s so much here … more than a thousand …,”

I mumble in confusion, collecting the fallen heap of hundred-ruble notes and a fistful of coins. I struck it big. Going to Moscow for the day.

Sveta, Autumn 2020

Plaid

Colomna is the largest, most ancient and most secretive city in the Moscow region. As a child, I spent every summer at our dacha southeast of Moscow—even taking the same train, which means that the butterflies are the same here as they were when I was little. But I had never been to Colomna before, perhaps because it was off limits due to the military factories there. Misha likes to say that Colomna’s fate is much like Venice’s: it was once a powerful commercial and defensive city at the intersection of three rivers—the Moscow, Oka and Colomenka—and a major transportation hub on the route from Moscow to Persia and the Mediterranean, but after the rivers lost their importance, it withered and turned into a monument, a living ruin. Catherine the Great, struck by the beauty of Colomna, stopped the destructive practices of the locals, who were pulling apart the local kremlin’s stone walls for their own needs, and granted the city a regular plan. That was when Matvey Kazakov also took a liking to Colomna and drew it, contributing in no small part to its present-day museumification. The general plan allowed Colomna to preserve the structure of a medieval city, with a residential kremlin and the gridded posad, along with external settlements.

We live in the posad, an area once inhabited by craftsmen and merchants. When you see a house angled away from the street, that means it’s from the pre-Catherine period. On the right, across the street, there’s a solid fence from behind which you can sometimes hear drumrolls and marches. This is a large, closed-off section of the posad that cuts our street in two. The old women here love talking about the incredible beauty of the old mansions that belonged to famous local merchants, now hidden behind military fences. In 1941, the Leningrad Artillery Academy was moved here, and now it’s an unmanned flight center. Across from it is a “communal” manor house; all the old stone houses here became communal, with their massive marble staircases replaced by narrow wooden ones, whether to expand the amount of livable space or to eliminate the inequality between the comrades who lived in these palaces and those who didn’t. On the left is the Church of the Epiphany, Italianate in form but bright blue in color. It was the only functioning church in the Soviet period. On holidays and Sundays, we’re woken up by the bells. Further to the left is our grumpy neighbor’s giant henhouse and, in the distance, the Kazan Railway. When a train with more than forty cars goes by, the second floor of our house rocks like a cradle. Life is full of sounds; I find it calming.

Sasha, July 2021

***

The door to the refectory of the Old Golutvin Monastery “asks” that you not feed or let in cats. Two grey bandits had already attacked me while I was talking on the phone. One sneakily climbed under my puffer coat and started climbing my leg. I shook him off, but he shot a piercing look at me.

It was crisp and cold outside, but the refectory was warm. As I was paying for my Lipton tea, a red-haired novice walked in, carrying an old microwave.

“Hey, Tanya, I brought this for you. I gave an old lady a ride, and she gave me this thing.”

He opens the door of the microwave and pulls out a plastic bag. He removes hand-painted bottles decorated with rhinestones and an enormous bag of coffee.

“The old lady paints the bottles herself! Really beautiful! Here, take it.”

He offers me one bright yellow bottle. Some saint peers at me from the label, but rest assured, the look on the cat from the street was far more severe.

“Thanks, but what is it for?”

“You can get holy water in the church.”

He replaces the old microwave on the counter with the “new old” one. Tanya carefully sets the bottles out on the shelf. I write a note on my phone. A red-cheeked priest comes in from the cold. I’ve been afraid of priests since I was little, so I automatically hide my phone like a schoolgirl.

“Tanya, they brought tuna! I’m going to go clean it now. We’ll put it out tomorrow.”

A visitor in a shawl asks,

“Father, how do you cook it? Tuna, I mean. It always falls apart on me.”

“It should be partially frozen. You cut it into big pieces and sear it on both sides; otherwise, it falls apart.”

Sveta, January 2021

Polka Dots

Among the decorative elements of wooden houses and gates in Colomna, you see a lot of solar symbols cut out of wood. Ridges like pleats radiate out from the center. They’re usually ornamental, but I’ll make a big circle like that on our gate—you’ll enter through a grey sun.

We came here almost a year ago to wait out the quarantine and keep an eye on the renovation work that had to be done on the house. Before I left, I asked Sveta out of the blue whether she and Mitya wanted to spend the winter in Colomna too, and Sveta answered that Mitya couldn’t, but she’d come. That winter, Sveta said we had to do an exhibition together since we were in isolation together, and I was going over to Sveta’s to work anyway. The apartment we rented while the renovations were under way was very small and dark, barely big enough for the four of us, with the children going to school online and Misha giving lectures over Zoom. Everything in the city was closed for quarantine, aside from a kebab place and a doughnut shop on Zhitnaya Square owned by two friendly guys both named Kostya. In the course of everyday life, we had only the Kostyas to talk to; our neighbors wouldn’t say hello and the city either was either rejecting us or didn’t notice us.

Once, when our elder son, Petya, was around six, he asked Misha to take him to work at his publishing house. They came back, both a little sullen, and I asked, “So, Petya, did you like it at work with Dad?”

“No.”

“You probably spoke with some of Dad’s colleagues, right?”

“No, they were working and didn’t talk to me.”

“Well, what did you see? Are there lots of interesting books there?”

“They’re the same books we have at home. It wasn’t interesting.”

“So you went there for nothing?”

“No! I wanted to look at the situation. I really like looking at situations.”

During our Colomna quarantine, Sveta decided to communicate with the world through Avito, the Russian eBay. She “looked at situations,” and in the evenings she recounted sketches of spaces and people.

Sasha, July 2021

***

Alexandra Alexandrovna’s treasure house Plates (that’s what it’s called in the phone book) is barely visible on the Colomna Avito, as though it had been intentionally buried under military jackets, the collected works of Fenimore Cooper and plastic trinkets. I happened upon it with the help of a plate decorated with blue cornflowers. On the phone, Alexandra gave me her exact address and I set off in search of clinking plates to the very end of Ivanovskaya Street. The entrance was through the garage and was guarded by a friendly little pug. The pug wasn’t allowed into the realm of plates above, where a triumvirate of cats presided. And there they are! With flowers, polka dots, chipped and worn, with crackle, from the nineties … in short, plate heaven. If you turn them over, you’ll see a Verbilki elk on some; others boast their Kuznetsk lineage; on one nameless plate, two blue drops seemed to have dripped off the blue rim into the white interior. Alexandra recalled the Colomna of her youth:

“In the winter, we walked home from school right past the ‘saucer’ (the observation platform in the Kremlin), but there was an abandoned brick building there back then. And there wasn’t any grass on the hill like there is now; it was all overgrown. We found a clear place between the branches and slid down. Once, while going home, I saw that one of my felt boots wasn’t shining in the dark. I had lost it and had to rummage around in the snowbanks and bushes until I found it.”

Golden and multicolored rims twirl and rush around Alexandra’s stories. Her son Konstantin came back from school.

“Mom, I lost my indoor slipper somewhere.”

I hurry home. It’s dark and deserted. A window in an old hut, visible all along Ivanovskaya, glows magenta, as though extraterrestrial agents were meeting there. Before I fell asleep, I wrote:

Song of the Plate

I remember from childhood

here in the village

the huts as if buried

grey dust on the facades

windows nailed shut

as though another civilization

just up and drowned

dunno

maybe you don’t believe me

what proof do you need?

Sveta, February 2021

Stripes

The city’s main street starts at the Square of Two Revolutions. To the left, the trading rows stretch along Zaitsev Street, parallel to the kremlin wall. An elegant Empire bell tower rises over the square, with a Dixy food store in its base. Another feature of the square is a strange, almost too realistic Lenin. For a large square, he’s unusually small, a little larger than life size, and not what you would call well-proportioned, with a wide pelvis and a more Asian face. This Lenin is an early example of monumental propaganda, created in 1926 by the sculptor Merkurov, the cousin of mystic philosopher George Gurdjieff and creator of the most significant unrealized Lenin on Earth, which was to crown the Palace of the Soviets.

I’m sitting in the apartment that Sveta rented on Zaitsev Street and reading her notes about recent events that we experienced together. Sveta only comes for visits now, and this is our shared studio. The two-story building from the nineteenth century, between Pyatnitsky Gate and the pontoon bridge, can boast that it was featured in the Brezhnev-era cult classic Diamonds for the Dictatorship of the Proletariat. In the evenings, at the height of our quarantine solitude, Misha got in the habit of watching films made in Colomna: there are a few hundred of them, starting with Eisenstein’s Strike and Alexander Nevsky.

The apartment looked awful when Sveta rented it: peeling lurex wallpaper from the nineties, metal bunk beds, rickety fiberboard furniture covered in fake-wood laminate and an old green couch that took up half a room. In spite of weak protests from Pavel, the landlord, Sveta decisively removed everything, stripped and painted the walls and even decorated the whitewashed hallway with uneven hand-painted stripes of unearthly beauty. None of the things from the house were thrown out: Pavel took them all somewhere. He doesn’t throw anything out. Pavel grumbled sadly that Sveta won’t ever earn enough to buy her own apartment if she goes on that way and that the next tenants may not want what we see as an objective improvement and something approaching aesthetically acceptable living conditions.

Sasha, July 2021

***

In Pavel’s house, under construction now for several years, each detail speaks volumes about incompleteness: a staircase without steps, a floor that can’t be walked on, disconnected radiators and couches heaped with things. In other words, a construction site. Amidst the bewildering chaos of household objects, Pavel stands tall: he pulls a functional old chair out of the motley mess.

Pavel sits on it and announces proudly: “This is my favorite thing here, you know.”

Sveta, April 2021

Pied-de-poule

When we first walked into our future home, the wooden boards by the entrance greeted us with a faint inscription in chalk: “I’m at Katya’s.” Later, when we bought the house and began renovating, Katya came to see us: she turned out to be very elderly, a distant relative of the deceased woman who had owned part of the house. Ekaterina Mikhailovna brought us a gift: a folder with plans of the house and all the documents dating back to 1912, as well as a metal placard with the number 13 from the sixties—the same as on the facade, but in pristine condition. The folder had a tenant book with the names of everyone who had lived there over the course of the twentieth century in different quantities and configurations: the once-private home had been turned into a communal house, then into two apartments. Next to each name, it was noted where the person came from and their trade. There was also a pile of denunciations that the neighbors had written about each other concerning domestic issues. I framed and hung the 1912 plans: they were drawn in various colors of ink, with yellow and white washes on yellowed paper. Quite beautiful.

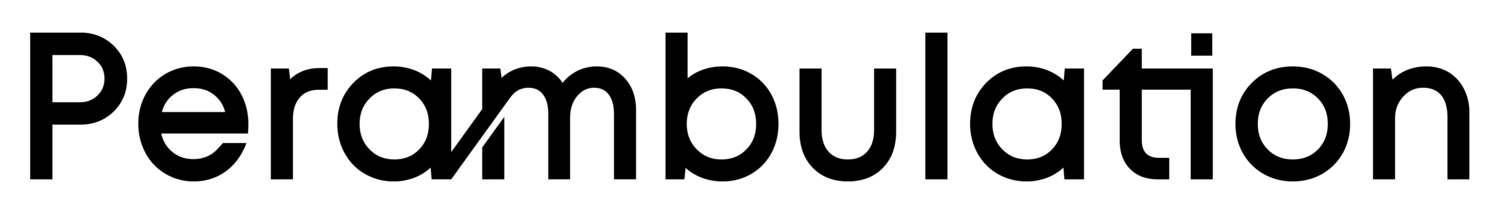

One January evening, Liza Plavinskaya tapped on the window: she finally made it here for a visit, but her phone died on the road and we didn’t have a doorbell. At the time, I was walking around a trunk that we had dragged out of the barn along with the rest of the furniture and wondering how to clean it. When we bought the house, there were two owners. The old woman who owned part of the first floor took all her lacquered cabinets and tables from the seventies to her grandson’s. The rest of the house belonged to Maria Ivanovna Burberry, who was born on Ceylon and lived near London, and her two nephews, the children of her late sister. By the looks of things, the family had strained relations, so two thirds of the house had lain empty since 1992, and time had clearly stopped: wallpaper from the sixties, late Soviet wall calendars and a map of the USSR that was the main reason our older son, Petya, wanted to buy the house: he loves looking at and drawing maps. At first we thought we had bought an empty house, then went into the barn and found out there was enough to furnish the place: an old table, bentwood chairs, a wardrobe, carafes and bottles, a cupboard, mirrors

***

Liza sat down for tea and rested from the trip while giving me valuable advice on cleaning the dirt and rust off the trunk. The rust had to be coated with tomato paste and left overnight. The paper that lined the trunk had to be stripped out; otherwise it would always smell moldy. A brown envelope was stuck to the inside. I pulled it off, opened it and froze: there was a stack of old photographs of people in coffins. A pretty girl lay surrounded by white flowers. A young man and others in winter clothing stood around the coffin; a child, who might have been a boy or a girl under the winter clothes, looked at the body and huddled next to an adult. Liza, with her characteristic lightness, exclaimed, “That’s so beautiful! Don’t be scared—back then, funeral photos were horribly fashionable!” But you can’t say for certain when these photos were taken, since the people were in peasant dress with no hint of fashion or time period.

***

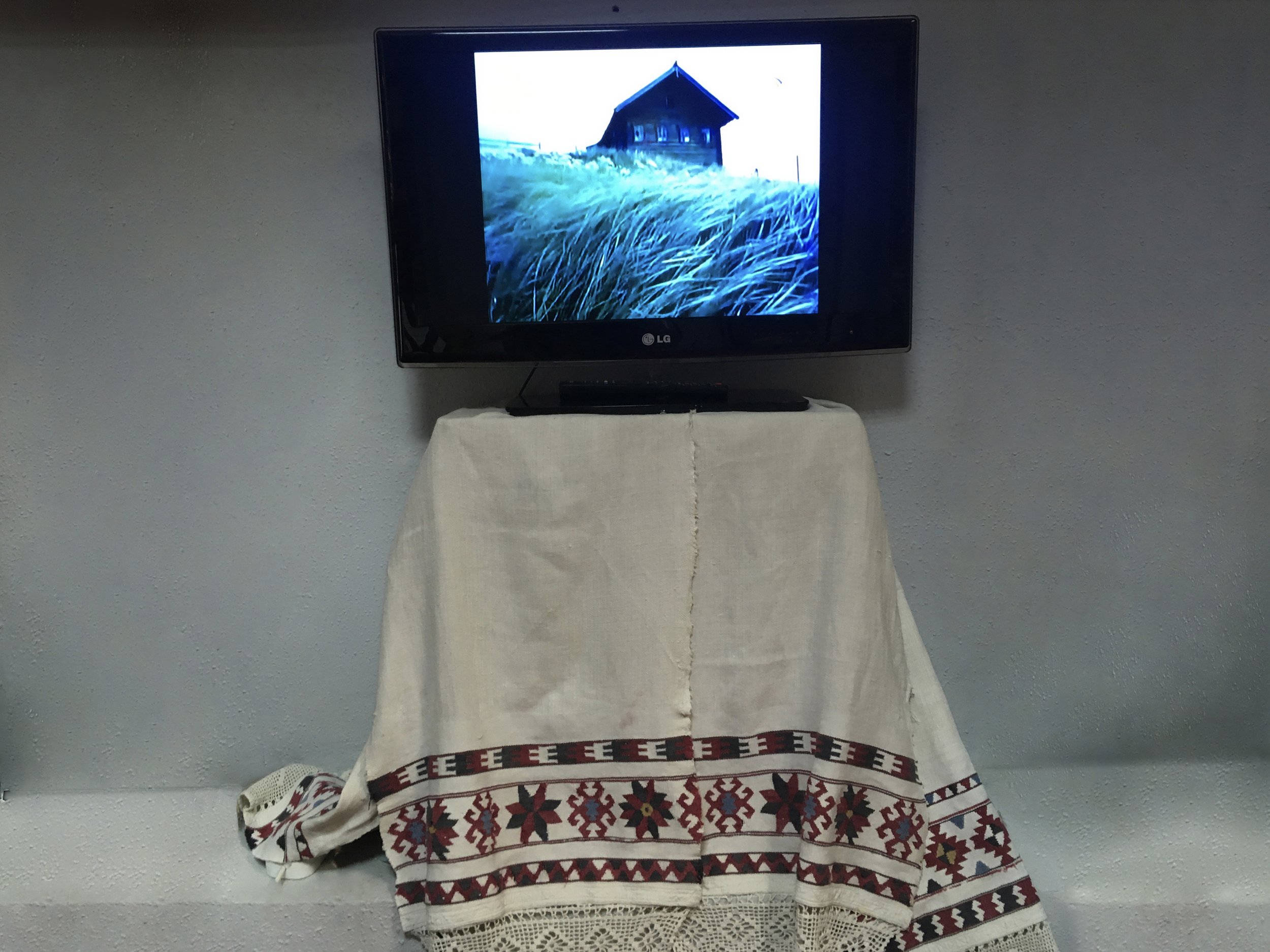

The dark silhouette of elderly Melania ambled through a snowstorm to the Church of the Epiphany for services. Her name came to her from afar, from ancient Greece, and translates as black or dark. Nobody knows where Melania came from or where she lives.

Sometimes she turns her warmly wrapped head towards a house, as though she were looking into the windows’ eyes, squinting and smiling.

“A good little house. Alive. Maybe I could find a place for myself there too,” she mumbles.

The decoratively framed windows are indeed alive, Christmas lights blinking like candles flickering in the wind. The house and the old woman look at each other, each taking the other in.

Sveta, January 2021

Rhombi

In the kremlin by the walls of the Novo-Golutvin Monastery, the Museum of Organic Culture is located in a wooden house with openwork window frames. The mysterious name either gives passing tourists a laugh or piques their curiosity, but there’s no rush to sell tickets to the uninitiated. If a guest at the door can assure the quiet woman in a long skirt that they’ve indeed come to see Matyushin and Sterligov, she graciously opens the doors and shows them all the books published by the museum. Inside are paintings, paint samples, jars of pigments from the Matyushin studio, driftwood, Suetin furniture and reconstructions of wooden musical instruments styled as simplified geometrical shapes. In the last room, another woman in a long skirt walks over to a frame hidden by mica paper and ceremoniously lifts the paper to expose Matyushin’s “Soundcolor.” This is a temple to the organic branch of the Russian avant-garde.

***

The old windows turned out to be priceless. Never mind that I had already managed to forget what a wonderful thing the small ventilation windows called fortochkas are. There was also very old crooked glass that creates caustic patterns like those in water when street lamps shine through it. Everything is crooked here, from the walls to the floors. The angle seems minimal, but I was nauseous for the first month in the house, like the first few days you spend in Venice. We kept on fixing our beautiful crooked house, but everyone from a gas company technician installing meters to a service man from the city water supply—pleasingly named “Colomna Warmth”—makes a point of asking, “Did you buy it for demolition?” For the most part, the people working on our house see it as a Moscow caprice—some with sympathy, others with annoyance.

In the autumn, we sometimes made a bonfire in our garden: we burned enormous piles of old boards and wallpaper and dry weeds. Sveta would throw potatoes and eggplant wrapped in foil into the coals. Petya and Vasya retrieved little curiosities for their archaeological museum and painstakingly laid them out along the fence. As night fell, we dragged the last glowing embers out into the grass and watched the flickering metropolis scattered around our autumn garden.

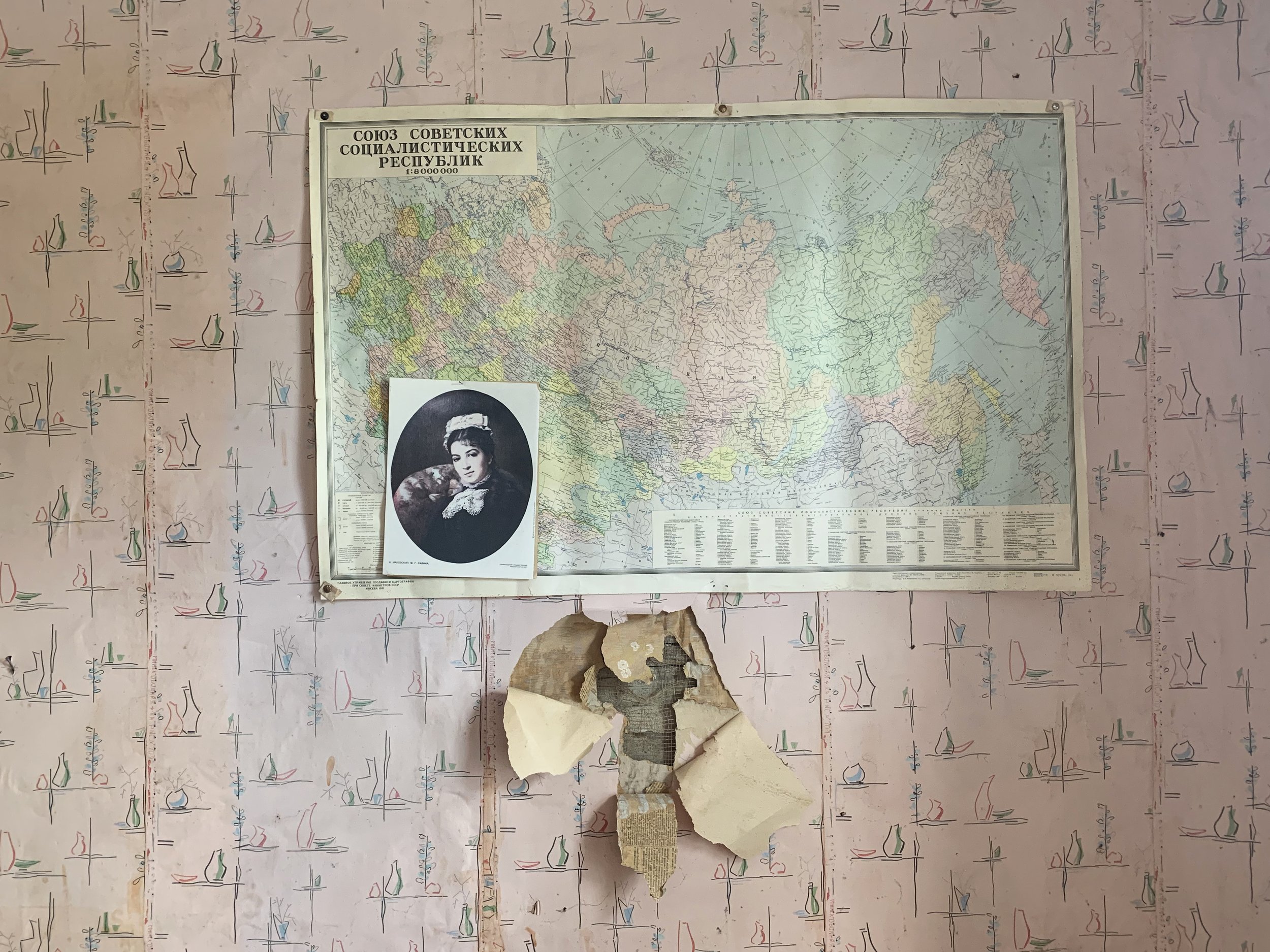

Sveta learned to make stained glass. She went to Moscow and bought beautiful tools from Japan and Germany and colored glass from America and China. She’ll make glass works for our exhibition, and she practiced by making us a housewarming gift: a stained glass piece consisting of rhombi for an old cabinet that we brought from our barn.

Sasha, August 2021

***

In Colomna, there are a lot of soldiers. Victor is one of them; he’s my neighbor. On weekday evenings, he plays computer games, and on weekends he talks to some woman on Skype and sings in a loud tenor voice. Through the wall, I can hear him giving loud orders to his digital soldiers and monstrously growling in defeat and at other times singing his favorite song. Shazam said that it’s by some group named NoAngels. Loudly singing the whole song along with the group, Victor puts special emphasis on these lines:

What will come after doesn’t matter at all

What came before doesn’t matter now

Don’t have to think ’bout anything at all

We own the whole world now

Sveta, Spring 2021

Bright

Once, after waking up early in the Italian town of Possagno in a hotel that shared a rundown seventeenth-century villa with a post office and a little coffeeshop, I went down for breakfast and saw lots of old men with cups redolent of coffee and grappa. The men were all talking among themselves, either before work or instead of work. I thought how interesting it would be to live in a small town. I grew up and always lived in big cities: Moscow, Chicago, Philadelphia, New York, Paris. And now, in Colomna, I really feel the difference between tourism and emigration and know that any large city makes more sense to me. Never mind that Colomna is only some fifty kilometers from the places of my childhood.

I come out of the house, ride my bike toward the kremlin on my way to the studio, and my former selves—tourists—are all around. They look at me and think how interesting it would be to live here. I’m interested too. I haven’t figured out anything yet.

Sasha, August 2021

***

I can’t get to sleep without flipping through the “news” on Avito. An endless feed of fur hats, chairs, irons, dogs, cats, an Olympic bear, a house with 2,300 square meters of land, clear agates, plates, well diggers, saplings. Agates! Softly shaded, striped, clear. I write to Zlata and agree to meet her the next day.

Walking: I can never walk enough. I can walk far and for a long time. If someone paid me for every time I went wandering, I’d be a wealthy woman. I walked an hour and a half to see Zlata and her agates, through all of Colomna. She gave me a tiny bag with three stones at the bus station under the clock. I was a little upset that they were so small, but I didn’t back out of the deal. After stuffing the stones in my pocket, I walked on to the Staro-Golutvin monastery to look at Kazakov’s Masonic towers. The cats, the refectory—I’ve written about them already, and it’s not interesting to write about churches.

Kazakov’s red-brick rocket-like towers stick up into the blue sky and guard the perimeter as they wait for nightfall. Behind the towers, almost brushing against them, freight trains trundle toward Ryazan. The monotonous drone of the lumbering trains lulls Colomna to sleep. The cold seemingly freezes the sound, which settles into a transparent droning mass. I emerge from the monastery’s walls and walk toward the intersection of the Moscow and Oka rivers. Frozen mud, yellow shreds of dry flowers and frozen puddles like agates. Giant icy agates—the exact ones I wanted. Lots of them, and belonging to no one.

Sveta, January 2021

***

We decided to call our exhibition “A House on Chicken Legs,” inspired by Baba Yaga’s house as a metaphor for liminal space—a frontier post between our world and the world beyond. The work really took off once we had the name. Sveta and I were walking beside the Colomenka, and I was suddenly struck by the most vivid memory I have connected to Baba Yaga. I had a great-grandmother named Manya, as old as the century itself: she was born on December 31, 1900. I spent lots of time with her as a child and sometimes shared a bedroom with her. Manya wasn’t highly educated: she was the oldest child in a big family that lost its father early. He left to find work in New York in the hopes of bringing his family over later, but then World War I broke out. He made the difficult journey home in steerage, contracting typhus along the way, and died after his return. I painted all the time and loved colors so much that I would express my feelings through color, and Manya came up with a daily series of tales about five Baba Yagas: the blue and green ones were wicked, the white and pink ones were good, and the Baba Yaga that was orange with black stripes was complicated.

Manya died when I was eleven. The adults decided not to take me to the funeral, so I gave my mother an envelope and asked her to put it in the grave. Mom asked if she could open the envelope and was surprised when she pulled out a blank sheet of paper. I explained that I had thought out a letter to Manya on that sheet. This seemed like the natural decision: after all, it was intended for Manya alone, and if it could reach her, there was no sense in writing the letters and words at all.

Sasha, August 2021

Alexandra Paperno (born in 1978, Moscow) studied at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art (New York), where she graduated in fine arts in 2000. In 2004 her first solo exhibition was held at the National Centre for Contemporary Arts (Moscow). Her project Star Maps was exhibited in 2006 at the Stella Art Gallery (Moscow). Among her recent solo exhibitions: “Self-love among the ruins” (Shchusev Museum of Architecture, Moscow, 2018), “Abolished Constellations” (Galerie Volker Diehl, Berlin, 2018), “On the Sleep Arrangement of the Sixth Five-Year Plan” (Center for Contemporary Culture “Smena”, Kazan, 2015). She was part of group exhibitions at Casa dei Tre Oci (Venice), Albertina Museum (Vienna), MAMbo (Bologna), among others. Alexandra has also participated in the Garage Museum Triennial, the Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art, the Prague Biennale, and the Ural Industrial Biennale. She lives and works in Moscow and Colomna.

Sveta Shuvaeva (born 1987, Bugulma) studied at the Samara State University of Architecture and Civil Engineering. Since 2008 she took part in the unofficial school of contemporary art of Vladimir Logutov and became an active participant in Samara art life, collaborating with local institutions: an independent association of artists “11 Rooms” and Victoria gallery. Since 2010 she has been living and working in Moscow. From 2011 to 2014 she was a resident at the Vladimir Smirnov and Konstantin Sorokin Foundation studio. In 2013 she opened a gallery “Svetlana” located in a wardrobe in a rented apartment. In 2016 Shuvaeva became the artist of the year at the Cosmoscow International Contemporary Art Fair where she created a special project “It’s Okey to Change Your Mind” which was later shown at the Triennial of Russian Contemporary Art at the Garage Museum (2017). Her exhibition “Lake View Limited Offer” was shown at the Moscow Museum of Contemporary Art (2018) and later at Museum of Modern Art (MuHKA), Antwerp (2019). In 2020. the V-A-C Foundation commissioned her illustrations for O. Wilde’s fairy tale “The Wonderful Rocket”.